Excess Island

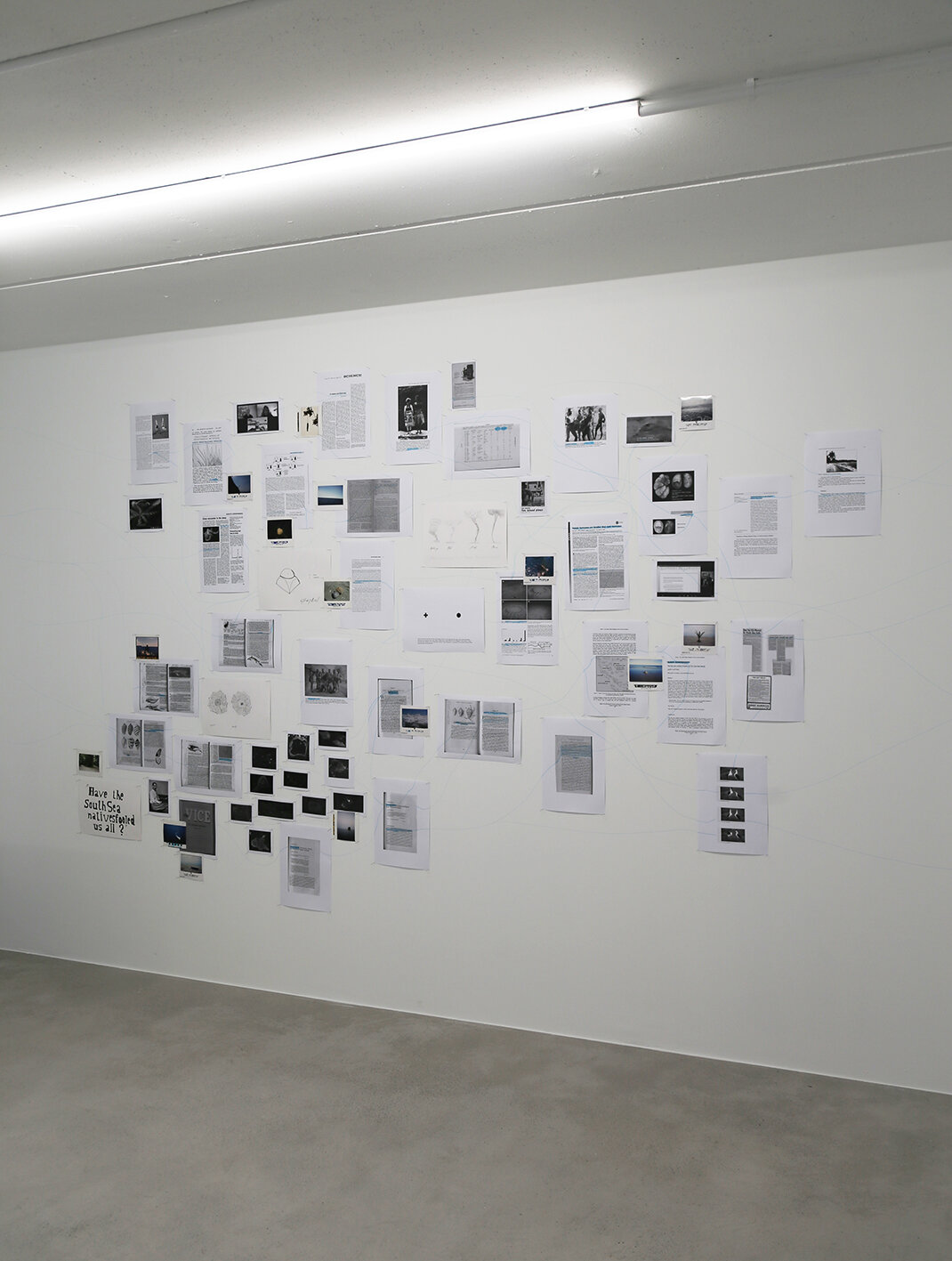

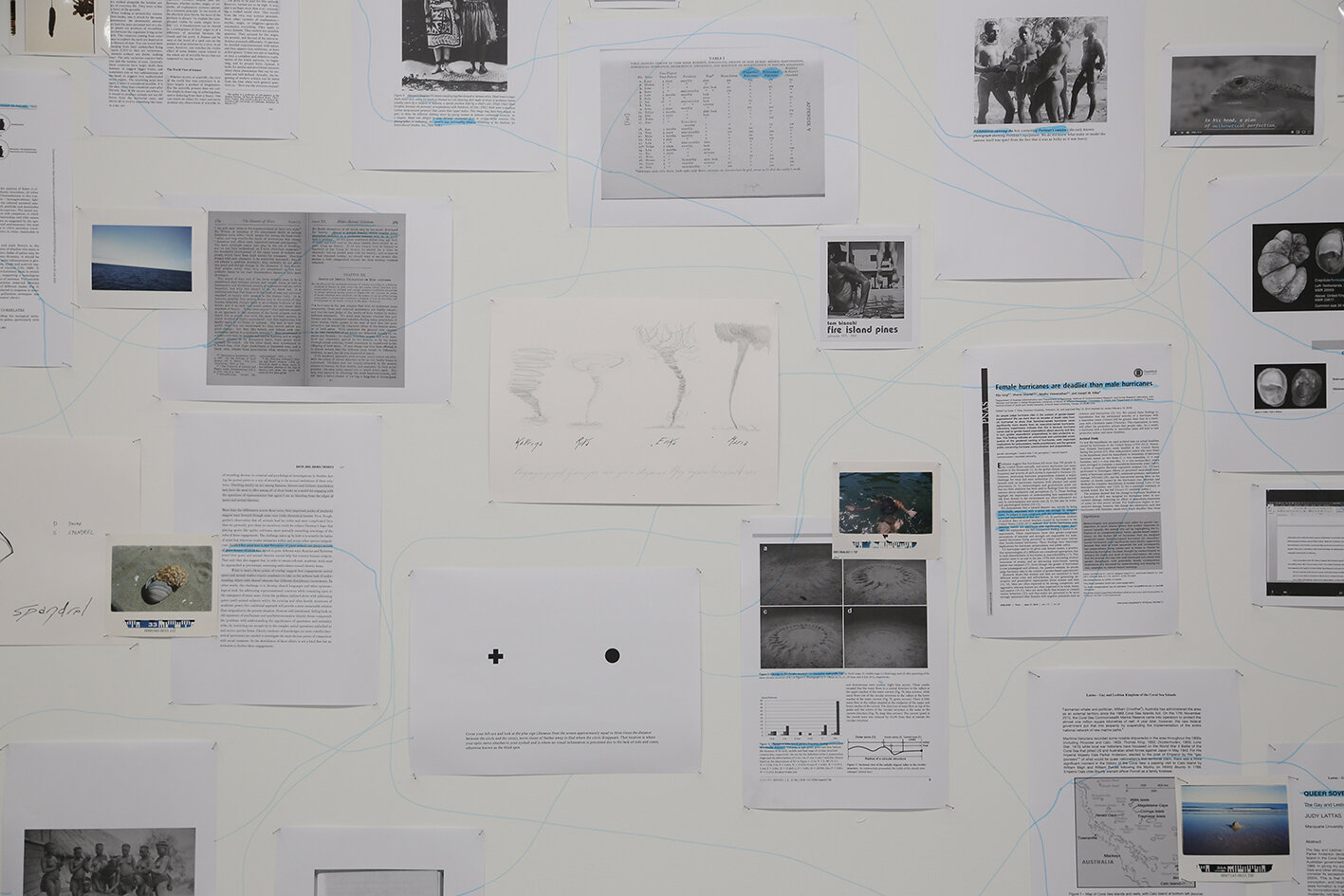

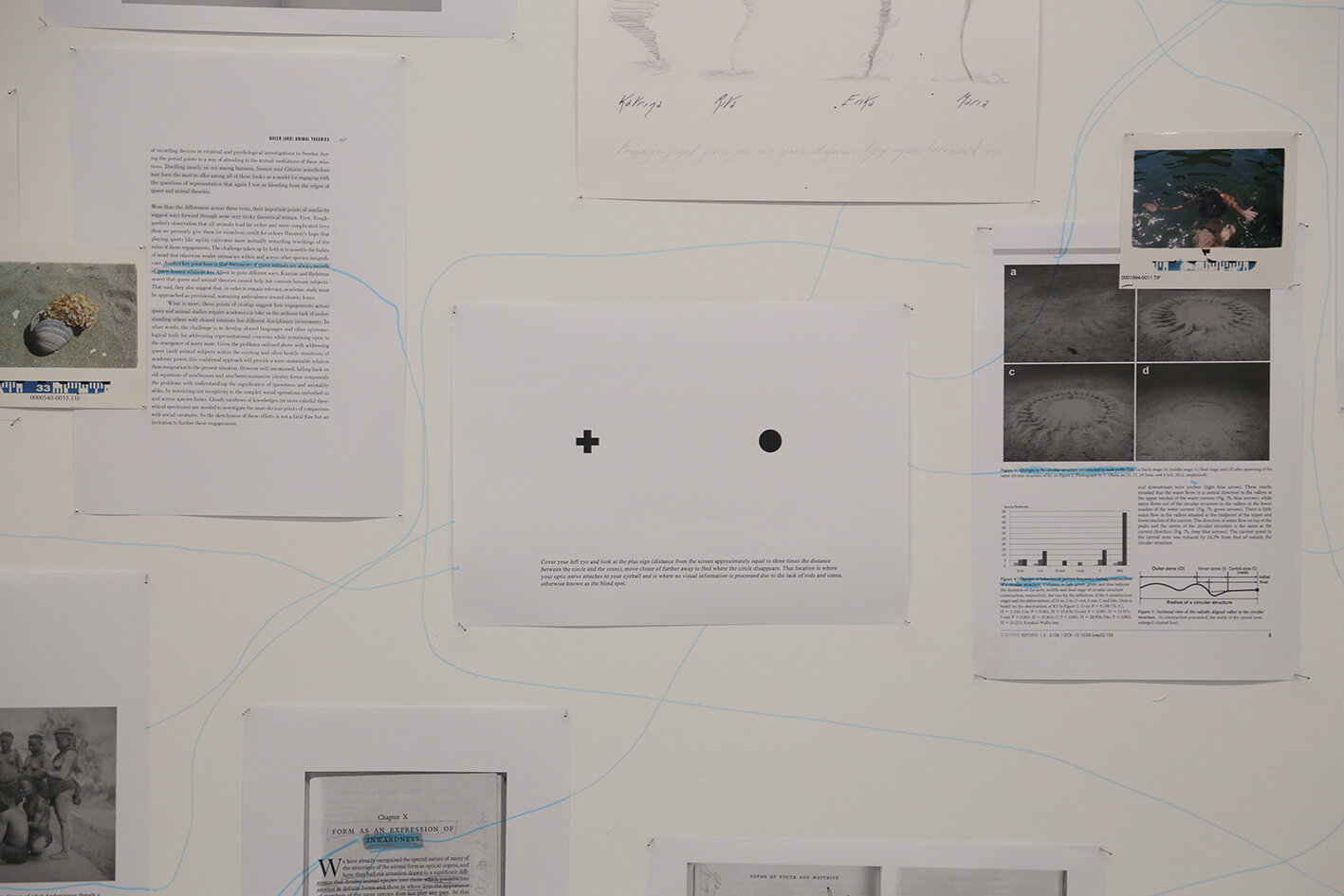

Excess Island (2011-2021) is a photographic project about an imaginary relation between the sea and the notion of sexuality. In this maritime territory gender, sexual notions, and practices, are spatialized and displaced. The notion of sexuality bends as a wave, waiting for that instant when it breaks on the seabed and skims. This project has to do with queering: horizons become a diagonal (from the German term quer) that cross and join apparently disjoint territories. Excess Island is the foundation of Panisson’s doctoral research project at Durham University, excavating, connecting, and confronting multiple genealogies of queer materiality, visual representation, and creative resistance across the planetary excess island.

Technical Details

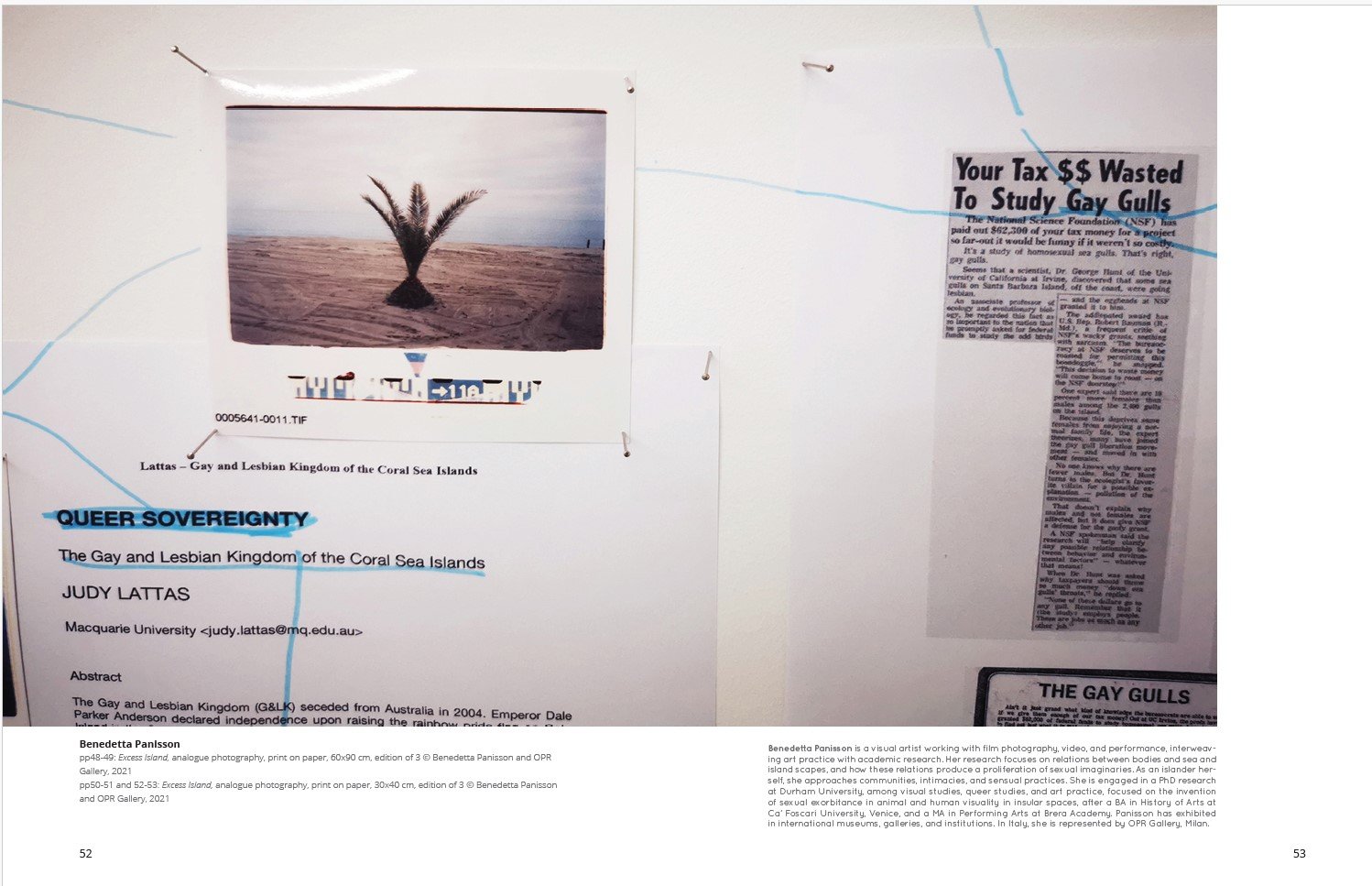

Color and b/w film photographic series, 69 images and handwritten texts. Variable dimensions. The project includes textual contributions from international academics.

Exhibitions / Collaborations / Publications

OPR Gallery, Milano, Onassis Cultural Centre; Antennae Journal, Queering Nature, Issue #63, curated by Giovanni Aloi; Athens, "Structures of Revenge", art exhibition/academic forum; Odesa Photo Days Festival, Ukraine; Phroom, Authorials; TEA Tenerife Espacio de las Artes, Canary Islands, Spain; Der Greif, Artist-Feature web selection; Cosmos, Arles, “The Family of No Man”, exhibition; Salon Ligne Roset, public talk with Tommaso Cotroneo adn art:i:curate, London. Durham University, UK.

OPR Gallery presents Excess Island, a solo show by Benedetta Panisson curated by Francisco-J. Hernández Adrián (Durham University, UK) in collaboration with Giangiacomo Cirla (OPR Gallery and PHROOM, Milan). Excess Island culminates a decade-long investigation into sensory poiesis and photographic emotiveness that documents acts of co-constitutive recognition between two modern protagonists: the voluble, sexual, camera-wielding human, and the sublime, refractive, and potentially hostile biosphere. In this imaginary and photographed relation, who makes what and who constitutes whom?

Excess Island suspends the impetus to commodify environmental objects and investigates sensing and coexisting on the margins of accelerated consumerism. Panisson’s photographs do not transact in exoticism, but embrace a reparative sense of self and place. As island environments grow increasingly constrained by material and audiovisual occlusions, these photographs evoke creative resistance and responsible action for the sake of multiple forms of life, personae, and sensuous pleasures that can open up fresh affective and conceptual passages. Panisson’s sensory islandscapes demand our participation in an unproductive, queer, and reparative future of intimate relation. The camera is already there, and Panisson’s work makes this apparent with political urgency, aesthetic fluency, and a contagious and reparative optimism.

Informing Excess Island at OPR Gallery, Panisson’s PhD project at Durham University excavates, connects, and confronts multiple genealogies of queer materiality, visual representation, and creative resistance across the planetary excess island.

OPR Gallery

Viale Corsica, 99

20133 – Milano

https://officeprojectroom.com/

OPR Gallery presenta Excess Island, mostra personale di Benedetta Panisson curata da Francisco-J. Hernández Adrián (Durham University, UK) in collaborazione con Giangiacomo Cirla (OPR Gallery e PHROOM, Milano). Excess Island è il risultato di una ricerca decennale sulla poiesis sensoriale e fotografica che documenta atti di riconoscimento reciproco tra due protagonisti contemporanei: l'umano volubile, sessuale, che brandisce la macchina fotografica, e la biosfera sublime, rifrangente e potenzialmente ostile. In questa relazione immaginaria e fotografata, chi fa cosa e chi costituisce chi?

Excess Island sospende l'impulso a mercificare gli oggetti ambientali e indaga il sentire e il coesistere ai margini del consumismo accelerato. Le fotografie di Panisson non si muovono nell'esotismo, ma abbracciano un senso riparatore di sé e del luogo. Mentre gli ambienti insulari sono sempre più limitati da occlusioni materiali e audiovisive, queste fotografie evocano una resistenza creativa e un'azione responsabile a favore di forme multiple di vita, personae e piaceri sensuali che possono aprire nuovi passaggi affettivi e concettuali. I paesaggi insulari sensoriali di Panisson richiedono la nostra partecipazione a un futuro improduttivo, queer e riparativo della relazione intima. La macchina fotografica è già lì, e il lavoro di Panisson lo rende evidente con urgenza politica, fluidità estetica e un ottimismo contagioso e riparatore.

Excess Island prende forma alla OPR Gallery, punto di partenza del dottorato di Panisson alla Durham University, un progetto di ricerca che scava, connette e affronta genealogie multiple di materialità queer, rappresentazione visiva e resistenza creativa attraverso la planetaria isola dell'eccesso.

Excess Island | Solo Show at OPR Gallery | Milano | Sept-Nov 2021

Excess Island | Video installation detail | HD 3 min. loop | Solo Show at OPR Gallery | Milano |2021

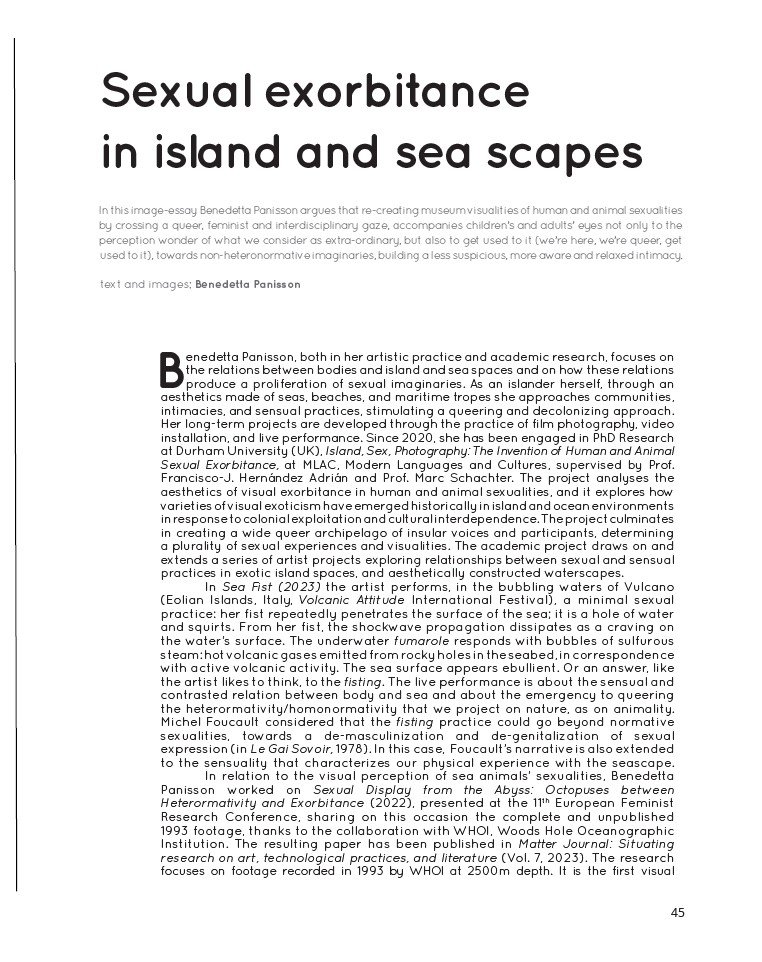

Difficult Intimacy: Photographic Immersions in Benedetta Panisson’s Excess Island

by Francisco-J. Hernández Adrián (Durham University, UK)

No less acute than a paranoid position, no less realistic, no less attached to a project of survival, and neither less nor more delusional or fantasmatic, the reparative reading position undertakes a different range of affects, ambitions, and risks. What we can best learn from such practices are, perhaps, the many ways selves and communities succeed in extracting sustenance from the objects of a culture – even of a culture whose avowed desire has often been not to sustain them.

Eve Sedgwick

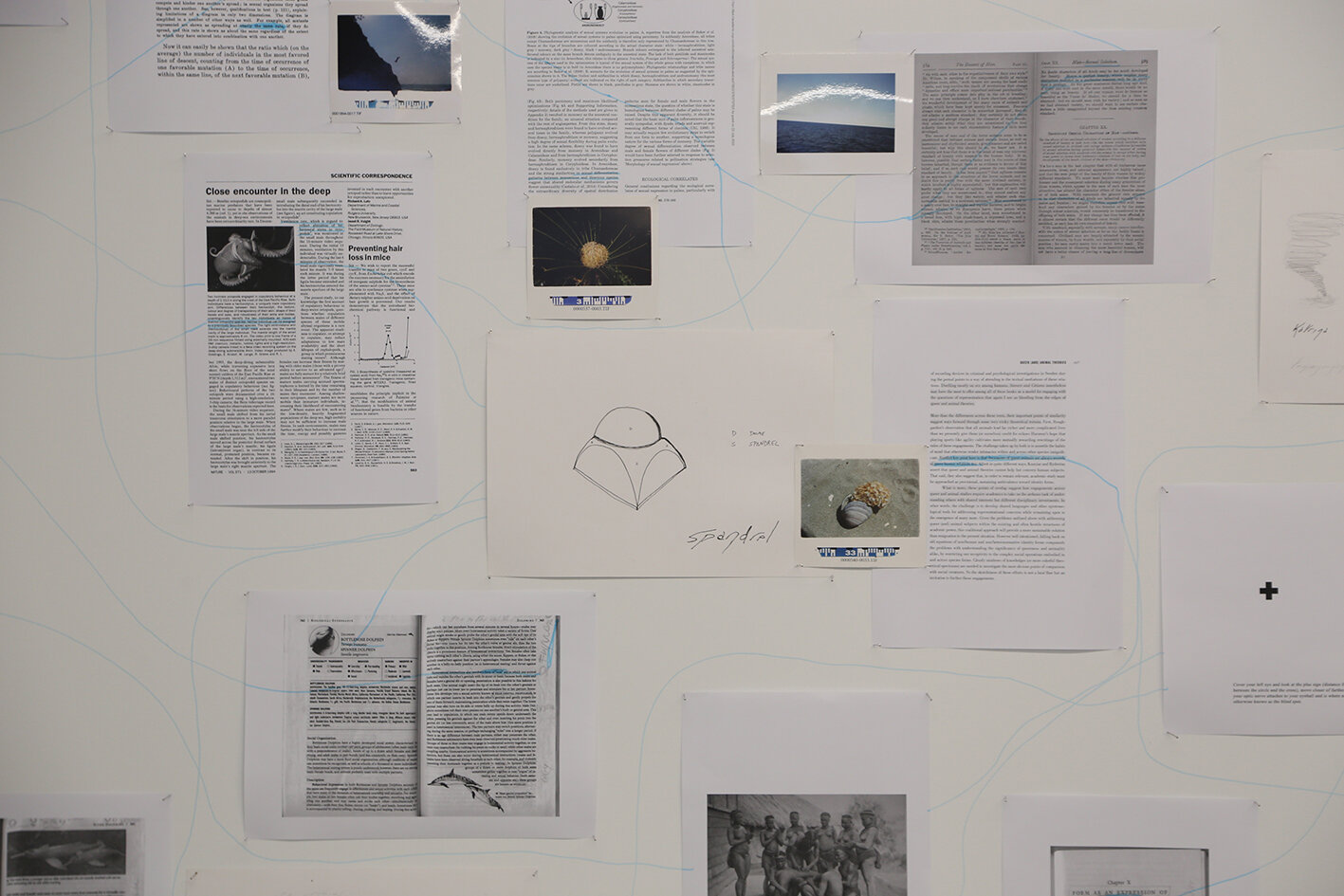

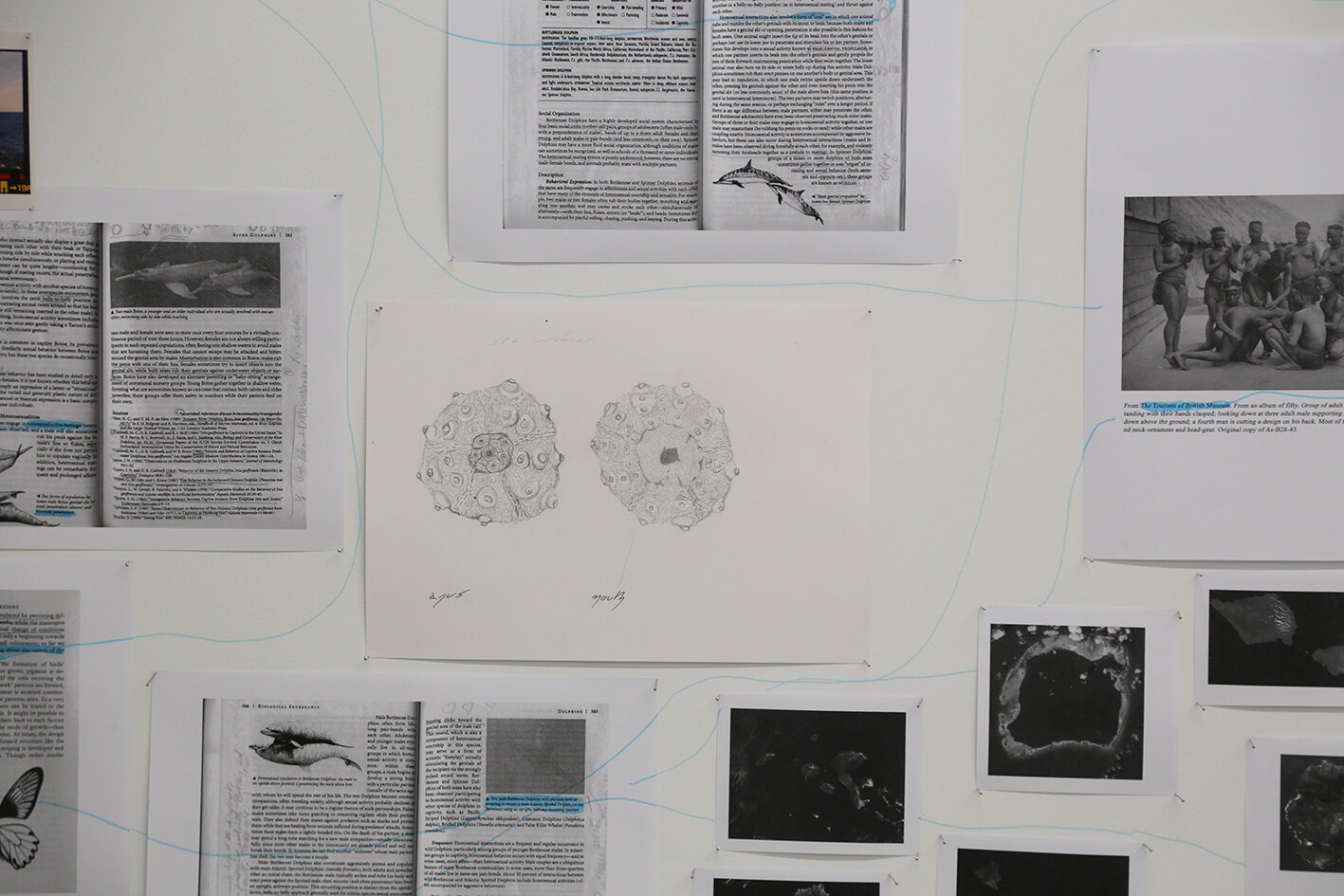

Excess Island culminates a decade-long investigation into sensory poiesis and photographic emotiveness that locates Western ways of seeing islands in what Eve Sedgwick, quoting Melanie Klein, calls “the reparative reading position.” The photographs that Panisson exhibits at OPR Gallery in Milan from September 2021 document acts of co-constitutive creation and recognition between two modern protagonists: the voluble, sexual, camera-wielding human, and the sublime, sentient, refractive, and potentially hostile biosphere. In this imaginary and photographed relation, who makes what and who constitutes whom? Panisson’s photographs display a thorough interrogation of the sensorium that lies beyond the common traveler’s sentimental reach because solitude and slow immersion are not usually included in the package holiday. Excess Island suspends the impetus to commodify environmental objects and demonstrates a commitment to sense and coexist on the margins of acceleration and consumerism.

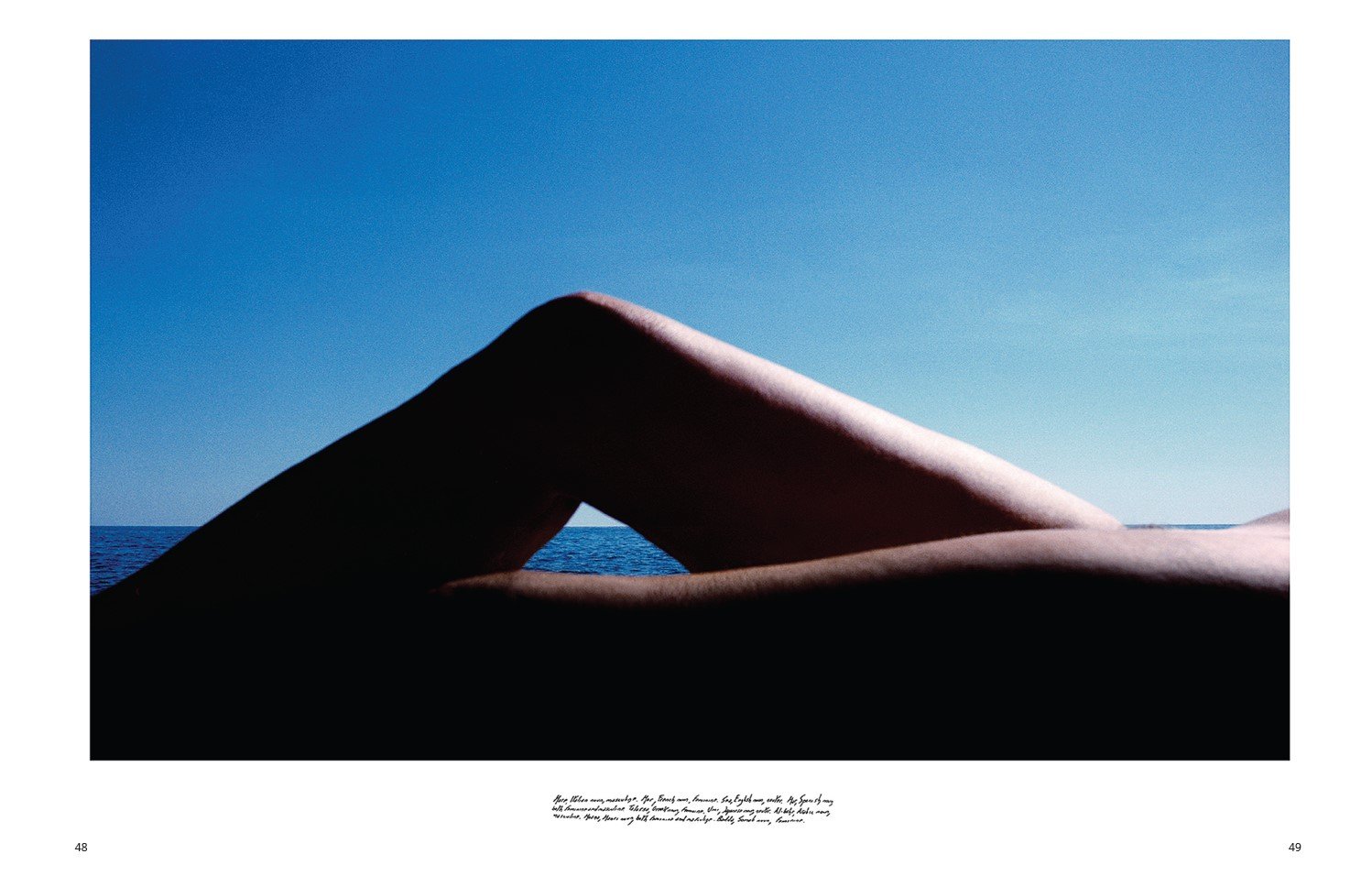

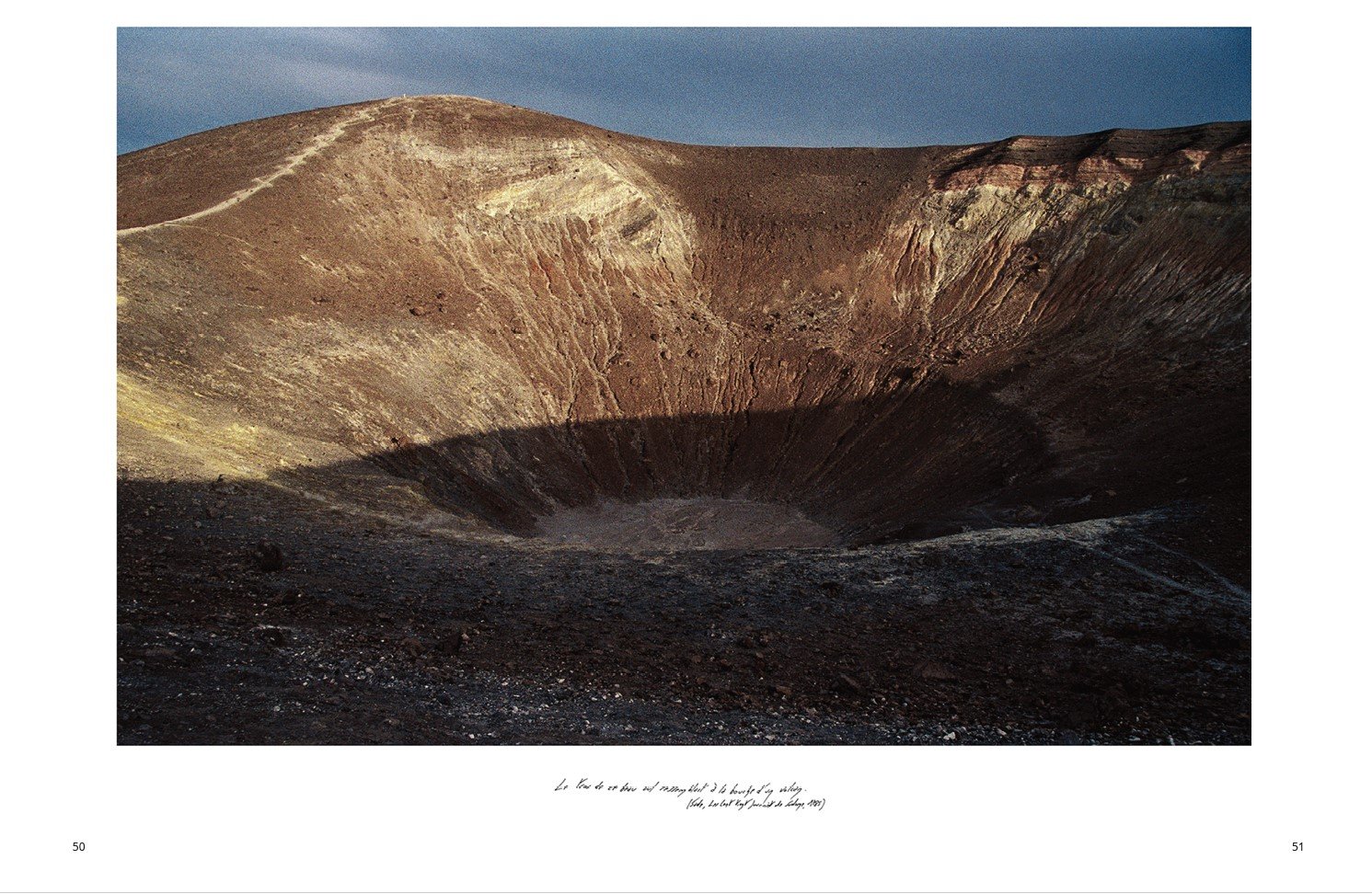

These are almost invariably diurnal photographs that privilege contrast, shade, and subtle transitional moods. They are accented by an emotive colour palette that ranges from mineral (azurite and sulphur), to twilight and dawn (pale pink and light blue), to analog silvers and deep blacks. They include variations on light and airiness, glimpses of intense diurnal immersion, and occasional instances of overexposure. They dwell on the intimacy of the open air, the watchful perambulation of a found vista, and those scenes that fit photographic convention initially, but only to question it by amplifying the supreme importance of acts of passing – the barely perceptible passing of day, bird, child, cloud or wave. Scale is transported onto the realms of symbols and archetypes, but quickly re-figured as metaphoric, erotically-charged body-parts. And these parts of the traveler’s cultural baggage are the excessive, sentient, pulsating erotogenic zones that we carry and project onto the island. Panisson’s photographs chart and magnify the personal discovery of these expanding, folding, receding island regions. Yet they do not transact in exoticism, but participate in a reparative sense of self and place. Their reach is at once is island-bound and planetary.

The photographic sequences of Excess Island express a determination to transcend the cultural construction of natural light through photographic processes. They represent an investigation into primordial freedom, an art of immersion that questions the atmospheric conditions of instant, fleeting, and slow intimate intercourse in elemental spacetime. Waves swell, the sea rises and can be alluring and playful, or imposing on its littoral domains, and often exhilarating in its iodized moods of gentle and intention-less rhythms. Panisson’s photographs capture these elemental moods firmly and intuitively, not by extracting or leading, but by letting go of contextual detail so the pleasures and risks of cross-reflection can project a memorable encounter. These images examine how fleeting instances of unrecoverable time can be expanded through an excess of sensory discharges that structures the picture in the moment of capture.

These images are more experimental and exploratory than their apparent simplicity suggests. We will find no trace of the baroque articulations of the embattled senses that constitute the photographic asthetics of windsurfing, paragliding, or mountaineering. There is no amorous battle or epic struggle against the elements, but a placid pressure that measures the variable intensities of intimacy and detachment and rejects the relentless politics of metropolitan perspectivism that, as T. J. Demos argues, would explain the Anthropocene without attention to colonial, racist and gender violence, and capitalist exploitation. These are intimate portraits or sketches of un-representable experience that make us feel at ease with nude and vulnerable panoramas of the constructed seascape and islandscape. If we linger and listen, we understand that the sea, earth, and sky are no longer pure, except in our fantasies of an eternally discoverable planet. In Excess Island, the sea, earth, and sky bear the memory of future catastrophes.

These photographs narrate an expansive intimacy. The island assists the photographer in framing intimate atmospheres. But what are the insular areas of sensory pleasure in this decaying assemblage, in this frayed materiality? The sequences of this imaginary conversation expand under the deep blue skies, near the raucous waves, and in botanical and geological excursions that annotate the receding sounds of nature. A labour of intimate attention to the evidence of planetary turmoil commences in these echoing images, and we hear a multitude of palpitating orifices. Like our erotogenic mouths, the range of orifices that structure Excess Island like a reparative scaffolding are perceptive zones: generous receptacles, bearers of affective potential, emanators and receptors of libidinal relation. In Excess Island, the planetary environments onto which humans and other species project our bodily openings do not display a singular body, but a plethora of rhythmic cycles, events, and impending environmental transformations that pulsate like shoals of mouths and evoke the infant proto-languages that irrigate our sensory capacities.

The spectator will wonder if these images might not be photographic souvenirs, exotic images of loss and nostalgia. Or are they samples of a fast-disappearing modern imagination of the living planet? Svetlana Boym wrote tirelessly about displacement, exile, and nostalga. As we enter the emotional textures of pandemic, post-pandemic, and anticipatory “normality,” Boym’s reflections resonate uncannily with Panisson’s exhibition: “The illusion of complete belonging has been shattered. Yet, one discovers that there is still a lot to share. The foreign backdrop, the memory of past losses and recognition of transience do not obscure the shock of intimacy, but rather heighten the pleasure and intensity of surprise” (255). The uncompromising immediacy of Excess Island collapses and splinters across the multiple connective streams of photographic recognition, or what Boym identifies so perceptively as the shock of intimacy.

Glenn A. Albrecht imagines a nostalgia that struggles to find a sense of direction. Citing Albert Camus, he writes that ‘when the limits of one’s world, its laws and order, are destroyed by forces beyond one’s control, then home becomes not only toxic, it becomes “nostalgia without aim”.’ He explains: ‘I define “solastalgia” as the pain or distress caused by the ongoing loss of solace and the sense of desolation connected to the present state of one’s home and territory. It is the existential and lived experience of negative environmental change, manifest as an attack on one’s sense of place’ (34, 38). If Excess Island recovers a sense of belonging through an unesy identification with the “home” of analog photography, do we not discern in all these images a nostalgia for the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, or for the adventurous, twenty-decade-long process of photographic reproducibility? Watching some of these photographs, we remember that pre-digital world nostalgically, like a crumbling yet coherent shelter, like a now derelict common home.

The excess island interferes with the prescribed visualities of island exoticisms. Photographic prosopopoeia channels island voices, exertions, moods, and atmospheres. Island poses and eroticised environments in turn ventriloquize the capricious Planet that stares back at us with passionate indifference. In this relational interplay, we are all persons and we all perform as characters – the heroic seagull, the gathering storm, and the shoaling fish. Yet it is not the cast of characters that matters most, but the fact that all these photographs characterize us as spectators and co-participants in photographic nostalgia. These images capture and liberate experiences that lie outside exploitative regimes of production, reproduction, and dissemination: the “the compulsion of production” that Byung-Chul Han identifies as an overriding pathology of our neoliberal condition. Panisson’s sensory islandscapes demand our participation in the visionary images and soundscapes of an un-productive, queer, and reparative future of intimate relation.

There is no contemplative inaction in these photograhs, but an immersive and reparative longing (a longing for acts of “reparative reading” and “reparative knowing” in Sedgwick’s sense) to participate in the variable moods of the planet. Nor is there an obvious contrast, so common in contemporary island visualities, between packaged leisure and industrial extraction, the otium and negotium of tourist exploitation. These photographs wander to the limits of the gathering clouds, weather disturbances, atmospheric phenomena, meteora. They form sensory interstices, folds, and perspectives that long for undisturbed encounters with island lives that by turns fly, erupt, recede, and deflect interpelation. Panisson’s images reflect on our contemporary appetite for expansive action, acting, re-enactment and circulation. But they reduce the traveler’s activities to a minimum, concentrating instead on an immersive, reparative labour of intimacy and hope.

Excess Island exposes the telescopic perspectivism that so often occludes island specificities in visual and audiovisual representation to indulge travelers, tourists, spectators, and customers in the service areas of globalized “island environments” – those island pastiches that know neither irony nor camp. In this particular strategy, Panisson belongs to a diverse family of contemporary visual artists who simultaneously mistrust and reimage earth, water, and islandscapes: Carmela García, Laura Huertas, Torbjørn Rødland, Wolfgang Tillmans, among others. As island environments grow increasingly constrained by an aggressive material and audiovisual occlusion, Panisson’s photographs demand our commitment to creative resistance and resposible action for the sake of multiple forms of life, personae, and the kinds of sensuous plesures that can expand new affective and conceptual passages.

What are these affective and conceptual passages? They are sequences of pores, mouths, anuses, nostrils, eyes, urethras, vaginas, and erotogenic minds like shoals of fish and thickets of palmtrees. We approach these photographs as images of future immersion in the liveable, loveable, fearful, vulnearable Earth. The camera is already there, and Benedetta Panisson’s Excess Island demonstrates this with political urgency, aesthetic fluency, and a contagious and reparative optimism.

References

Glenn A. Albrecht, Earth Emotions: New Words for a New World, Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2019, p. 34, 38.

Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia, New York: Basic Books, 2001, p. 255.

J. Demos, Against the Anthropocene: Visual Culture and Environment Today, Berlin: Stenberg, 2017.

Byung-Chul Han, The Disappearance of Rituals, trans. Daniel Steuer, Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2020, p. 1-15.

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity, Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 2003, p. 150-1, 149.

ITALIAN VERSION https://oprgallery.it/excess-island/

Rooftop Talk @ OPR Gallery | with Tommaso Cotroneo (I Cotroneo Collection) | Milano | Dec 2021

An image from Excess Island is part of “The Family of No Man” curated by Brad Feuerhelm and Natasha Christia, Cosmos Arles, 2018.

http://thefamilyofnoman.com/infos.php

Horizonte, mar, exceso, exorbitancia | Excess Island and People do Water @ TEA | 2019

https://teatenerife.es/actividad/taller-horizonte-mar-exceso-exorbitancia/1993?fbclid=IwAR3fcDjX-aRmMH_EE2xPKKfLSvgcyekGNrCj_Gth4da_CX5-io-EaH6NUE4

Phroom | Authorials | 2019 | https://phroommagazine.com/hydrophilia/

Excess Island Draft Project at Der Greif: https://dergreif-online.de/artist-blog/the-excess-island/

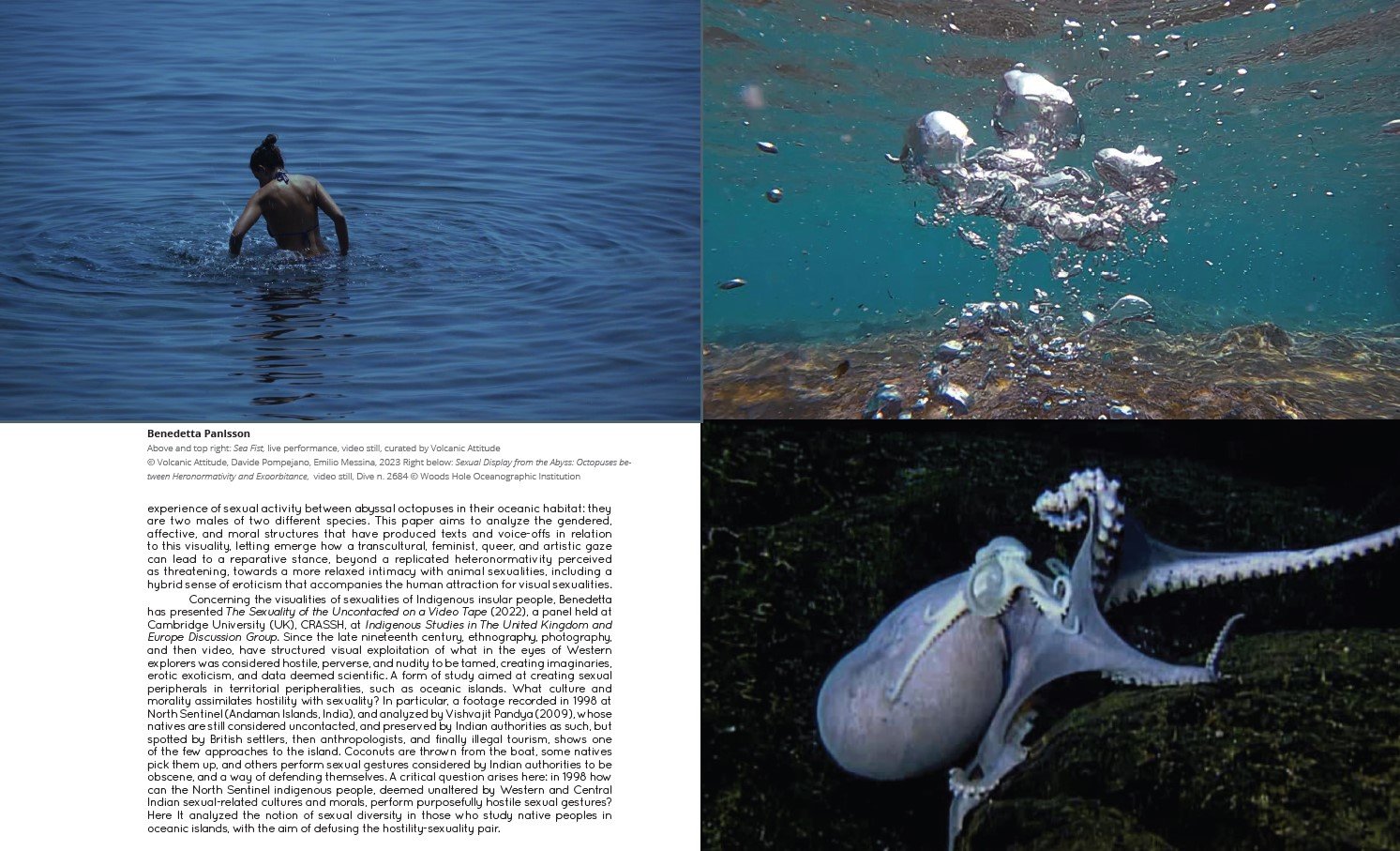

Sea Fist @ Antennae Journal | Queering Nature | Issue #63 | curated by Giovanni Aloi | https://www.antennae.org.uk/